ZScript_Basics

🔵 « Previous: Constants 🔵 » Next: Appendix 1: Flow Control

This chapter is a work-in-progress. To be revised/completed.

HUD and statusbar

Overview

A HUD (heads-up display) is various information displayed on the player’s screen, such as health, armor and ammo reserves. The aiming reticle and the pop-up messages are also a part of the HUD.

HUDs exist in the UI context, just like menus, which means they can read play-scope data but not modify it.

GZDoom supports 3 types of HUDs that can coexist and replaced:

-

Statusbar: usually the smallest HUD. GZDoom comes with a statusbar styled after the original Doom HUD that consists of a single graphic and some numbers drawn on top.

-

Fullscreen: the typical fullscreen HUD. GZDoom’s native fullscreen HUD doesn’t have any sort of background, providing better visibility, and spread things on the screen (such as displaying keys in the top right corner).

-

Alternative HUD: a special fullscreen HUD that is designed to override mod-specific HUDs. Uses custom scaling, so its size can’t be used-controlled. A custom alt HUD can be defined in ZScript, however.

Note that statusbar and fullscreen HUDs are actually one HUD, just switching between different modes. If you create your own HUD, you’re free to provide only one version of the HUD instead of two.

The alternative HUD, however, is a separate class that is drawn on top of the normal HUD. Properly defined regular and alt HUDs are designed in such a way that one of them simply stops displaying anything while the other is active, but they still exist at the same time.

Creating a HUD

HUDs have to be based on the BaseStatusBar class (you can find its source on GZDoom’s Github). Despite the name, it’s not just for statusbars, the fullscreen HUDs are also defined in it.

Alt HUD replacements, however, have to be based on the AltHUD class. This class is generally not particularly flexible, and thus mods rarely use it or try to override Alt HUD.

If you only want to add minor changes to an existing HUD, you can inherit from one of the vanilla HUDs (see GZDoom Github), such as DoomStatusBar.

A HUD is a regular ZScript class, so there’s nothing particularly special about its structure. Note that a HUD is not an actor, so it doesn’t have properties or the Default block like actors do. What you need to do is override various virtual functions to add your own behavior to your HUD. The basic structure of a HUD looks like this:

class MyCustomHUD : BaseStatusBar

{

// As with all ZScript classes, here you can

// declare class fields, constants and such.

override void Init()

{

// This function is called once, when the

// HUD is first created. Here you can

// define various default values.

// For example, HUD fonts are commonly

// created here.

}

override void Draw(int state, double ticFrac)

{

// This is where you draw the things you can

// see in the HUD. This function is called

// every frame, so the frequency of its calls

// depends on the player's framerate.

}

override void Tick()

{

// Similarly to actors, HUDs have this function,

// and it's called every tic, i.e. 35 times per

// second, regardless of framerate.

// You can't draw anything here, but it's good

// for things that need to happen on a fixed

// timed basis.

}

}

Init(), Draw() and Tick() are, of course, not all BaseStatusBar’s functions—you can find the full list and descriptions of the functions on ZDoom wiki. Most important things will happen in Draw(), however.

Add the HUD in MAPINFO

Technically, this should be done at the end of the whole thing, but I’ll mention it right here just so it doesn’t slip your attention: HUDs need to be added via MAPINFO. If you don’t do that, you won’t see your HUD.

There are 2 HUDs in the game that exist at the same time: the regular HUD and the alternative HUD. The latter gets drawn if the player enables the “Alternative HUD” option in GZDoom options menu. It’s possible to replace only one of those or both, although arguably it’s more common to only replace the base one and let the player use the classic alternative HUD if they desire.

In either case, you’ll need to use MAPINFO’s Gameinfo block to add those HUDs as follows:

Gameinfo

{

StatusBarClass = "MyBaseHUD"

AltHUDClass = "MyAltHUD"

}

…where “MyBaseHUD” and “MyAltHUD” are the actual class names of your HUD classes.

Note that GZDoom’s alternative HUD can be enforced by the player if they set the hud_althud_forceinternal CVAR to true.

Alternative HUD is a different type of HUD based on a different class: AltHud rather than BaseStatusBar. GZDoom’s alternative HUD is designed very differently from the classic HUD: it uses different scale and a bunch of custom functions for drawing. It’s documented on ZDoom Wiki but is rarely used for custom HUDs due to its fairly low flexibility. Most authors leave the players with an option to use AltHUD if they like. Note that both of these HUDs are drawn at the same time, and the base HUD has to explicitly stop drawing itself if AltHUD is enabled (this is covered further in the chapter).

Initialization

The first virtual you need to deal with is Init(). It’s called once, when the HUD is created (which is whenever the game is loaded) and is normally used to define various default values.

Structuring Draw()

There are several steps you need to take in order to properly draw things in your HUD.

1. Super.Draw()

First, you must call Super.Draw(state, ticFrac) before doing anything anything custom. If you don’t do that, the HUD will technically work, but a lot of things will be broken: messages won’t display/disappear propertly, the crosshair’s size won’t increase when picking up items, and so on.

2. Check HUD state

The second thing you need to do is check the value of state—it’s the first argument of Draw(). State (not related to actor states) has the following values: HUD_None, Hud_StatusBar, Hud_FullScreen and HUD_AltHud.

Based on these values you’ll need to decide what exactly to drawn since you can essentially have multiple variations of the same HUD. The basic idea is as follows:

HUD_None— the HUD is disabled by the player (e.g. by pressing the + key on the keyboard twice). Normally with this state you don’t want to draw anything, and you can simply call areturnand stop everything there:

override void Draw(int state, double TicFrac)

{

super.Draw(state, TicFrac);

if (state == HUD_None)

{

return;

}

// actual drawing stuff starts here

}

If you don’t add this exception, the player won’t be able to disable the HUD, it’ll still be drawn even if they keep pressing +. There’s no good reason to block this feature, so I don’t recommend doing that.

-

HUD_StatusBar— the player is using the minimal version of the HUD, aka the statusbar. In classic Doom this was the only existing HUD. In GZDoom statusbar is explicitly defined to only occupy the bottom part of the screen, 32 pixels tall (so, it’s 200x32 by default). However, this state doesn’t enforce any limitations by itself; it’s up to you to decide what to do with it. You can draw a proper, classic-style statusbar, separate from the fullscreen HUD. You can also draw the same things for fullscreen and statusbar states, essentially merging them into one HUD. You can also just make two separate HUDs, or make them similar but make the “statusbar” one into a minimal version. -

HUD_FullScreen— the player is using the fullscreen version of the HUD. This is arguably the most commonly used HUD nowadays and this is where you’ll likely focus most of your efforts. -

HUD_AltHud— the “Alternative HUD” option is enabled: the alternative HUD is being drawn. As mentioned earlier, the alternative HUD itself is a whole separate HUD class. What’s important is that GZDoom doesn’t switch between them; instead, whenstate == HUD_AltHud, the alternative HUD gets drawn on top of the base HUD, while the base HUD remains active. In other words, if you don’t want the HUDs to overlap, you need to make sure that in this state your base HUD is not drawing anything (or only draws some specific elements that don’t overlap the alternative HUD elements).

3. Begin the HUD

After getting the state (or maybe even before it) you’ll need to actually start the drawing process. Doing that requires calling one of the Begin* functions: BeginHUD() or BeginStatusBar(). These functions must be called before any of the actual drawing functions, such as DrawImage(). Let’s take a look at them.

void BeginStatusBar(bool forceScaled = false, int resW = -1, int resH = -1, int rel = -1)

BeginStatusBar() is used by the vanilla statusbar. This function defines a box area of specific size and places that box at the bottom center of the screen. The size of the box will adjust to screen size by default but it won’t change its aspect ratio (e.g. a 320x200 box will always be 4:3, so with a wider screen you’ll see a textured border at the sides).

What’s also important is that BeginStatusBar() will move up the viewport: meaning, the whole image of what you can see in the game will be moved up to make space for the statusbar.

The arguments work as follows:

-

bool forceScaled— if you passtrue, the HUD will always be drawn at the same size, ignoring all scaling options (meaning, the player won’t be able to scale the HUD using the “User interface scale” menu option). False by default. -

int resW— the width of the statusbar HUD box. The default value is-1which is interpreted as 320. -

int resH—the height of the statusbar HUD box. The default value is-1which is interpreted as 200. -

int rel— currently unused and shouldn’t be modified (defaults to-1).

void BeginHUD(double Alpha = 1., bool forcescaled = false, int resW = -1, int resH = -1)

BeginHUD() is normally used by the fullscreen HUD. In contrast to BeginStatusBar() it draws relative to screen corners (or center points of screen edges, if you prefer). This will give various drawing functions access to special flags that define relative positioning, which will guarantee your HUD will work in different aspect ratios (e.g. if you draw something in the bottom left corner, it’ll be there both on 4:3 and all the way up to 21:9). This function also doesn’t move the viewport.

The arguments are:

-

double Alpha— the alpha of the HUD, lets you make it translucent.1.0by default (fully opaque). -

bool forcescaled— works the same way as withBeginStatusBar(): draws the HUD at a fixed resolution and disablesthe ability to scale it. -

int resW— the virtual width of the fullscreen HUD. The default value is-1which is interpreted as 320. Note, the HUD will still scale to match screen resolution and aspect ratio. -

int resH— the virtual height of the fullscreen HUD. The default value is-1which is interpreted as 200. Note, the HUD will still scale to match screen resolution and aspect ratio.

Which one you need is a matter of design. The vanilla Doom HUD uses both, calling BeginStatusBar() if the state is HUD_StatusBar, and BeginHUD() for HUD_Fullscreen:

override void Draw (int state, double TicFrac)

{

Super.Draw (state, TicFrac);

if (state == HUD_StatusBar)

{

BeginStatusBar();

DrawMainBar (TicFrac);

}

else if (state == HUD_Fullscreen)

{

BeginHUD();

DrawFullScreenStuff ();

}

}

(See the full code on GZDoom repository)

However, it’s perfectly possible to only use BeginHUD() and then just manually decide what to draw based on the state. As mentioned in the previous point, your “statusbar” doesn’t have to be a literal statusbar, it can be just some sort of a minimal HUD but drawn using the same methods as the fullscreen one.

4. Start drawing

BaseStatusBar comes with many functions, but the ones you’ll be using most of all are, arguably, DrawString(), DrawImage(), DrawTexture() and DrawInventoryIcon().

Note that often those functions are packed into other functions just for the sake of convenience. For example, if we look again at the Draw() call from DoomStatusBar:

class MyHUD : BaseStatusBar

{

override void Draw (int state, double TicFrac)

{

Super.Draw (state, TicFrac);

if (state == HUD_StatusBar)

{

BeginStatusBar();

DrawMainBar (TicFrac);

}

else if (state == HUD_Fullscreen)

{

BeginHUD();

DrawFullScreenStuff ();

}

}

void DrawMainbar(double TicFrac)

{

// custom code to draw something in statusbar mode

}

void DrawFullScreenStuff ()

{

// custom code to draw something in fullscreen

}

}

The DrawMainBar() and DrawFullScreenStuff() functions are not drawing functions like DrawImage(); instead they’re simple custom void functions added to better structure the drawing. You don’t have to do it — there’s nothing stopping you from shoving everything inside different code blocks in Draw() — but it’s recommended to do something similar just to keep things more sensible. Of course, it’s up to you how to structure and name those functions.

The actual drawing is covered in more detail in the next subchapter.

Drawing in the HUD

Once your HUD class and Draw() are set up correctly, you can actually start drawing things, such as images, numbers, icons, bars, etc.

HUD element offsets

First, let’s talk about how elements (such as images, strings, etc.) are placed on the HUD. Note, for the examples we’ll be using DrawImage(), which is the simplest BaseStatusBar function that is designed to draw images.

All drawing functions have positions that define where the element will be drawn. These positions are offsets from a certain drawing position (which by default is the top left corner of the screen). For example, DrawImage()’s second argument is the position/offsets (as a vector2 value):

DrawImage("MEDIA0", (0, 0));

This will draw a medikit sprite at the top left corner of the HUD area. The starting point of the offsets aka (0, 0), is by default the top left corner. Positive X values will shift the point to the right, positive Y values shift it downwards — this is always true, regardless of the type of HUD and the use of offset-related flags.

As noted before, statusbar and fullscreen HUDs treat offsets differently.

Statusbar offsets

Statusbar-type HUDs (prefaced with BeginStatusBar()) draw stuff in a box of specific size. Usually the elements are drawn with explicit offsets from the top left corner. For example, the Doom statusbar is drawn within a 320x200 box, and the bar graphic is drawn at (0, 168) since the bar is exactly 32 pixels tall, so it covers the 32 bottom pixels of the box (the graphic itself is drawn starting from its top-left corner). Elements drawn in that statusbar are offset relative to the statusbar area, which is what BeginStatusBar() sets.

When the user changes their HUD size using “User interface scale” GZDoom option, statusbars don’t change their aspect ratio. For example, if you define a 320x200 statusbar but play on a 16:9 screen, you’ll see empty space on the sides.

Fullscreen offsets

In contrast, fullscreen HUDs (prefaced with BeginHUD()) are drawn along the whole screen, so (0, 0) points to the top left corner of the screen (by default), not a specific area. The size of the fullscreen HUD specified through BeginHUD() only defines the virtual canvas initially allocated for the HUD elements but does not actually correspond to screen resolution or aspect ratio. For example, if you define a 320x200 fullscreen HUD, the 320x200 area should be basically treated as a guide to how much space you have for your elements, which means the graphic elements should be initially designed with a 320x200 canvas in mind; however, it does not correspond to how much space you will actually have available: even when it’s scaled up to the screen size, the width will likely be above 320 and the height will be above 200 due to aspect ratio and screen size.

As such, explicit offsets like (0, 168), should never be used with fullscreen HUDs. Instead, elements should be aligned against specific anchor points, such as screen corners and edges. This can be achieved with the use of the various DI_SCREEN* and DI_ITEM* flags. All of these flags can be seen can be found in GZDoom GitHub repository, but they’re also documented on specific function pages on the wiki, for example DrawImage().

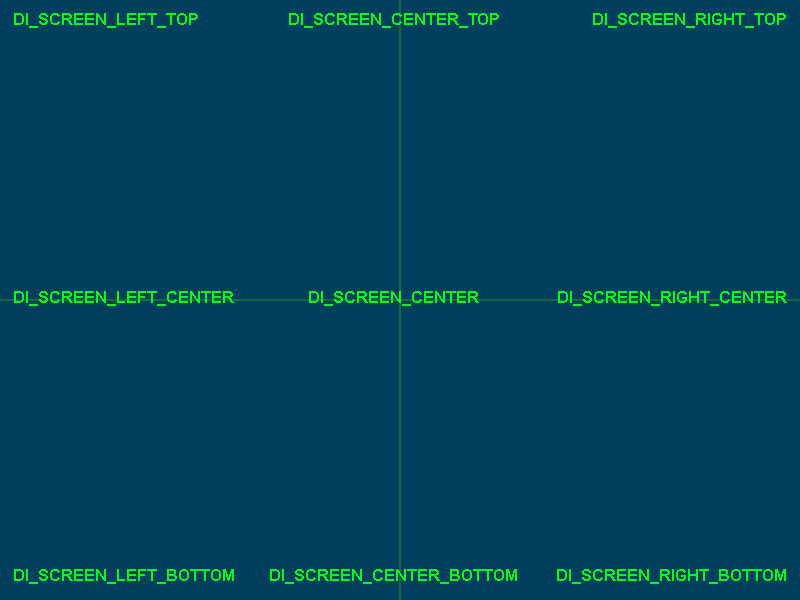

DI_SCREEN* flags define the starting point for the position coordinates. For example, DI_SCREEN_LEFT_TOP will define the left top corner as (0, 0), while DI_SCREEN_RIGHT_BOTTOM will define right bottom as such. Note, it doesn’t change the direction of the offsets: positive X is still down and positive Y is still right; it only changes the position of the starting point. This means that, if you use DI_SCREEN_RIGHT_BOTTOM, you basically have to use (0, 0) or negative values to go upward and leftward, since positive values will shift the element beyond the screen edges.

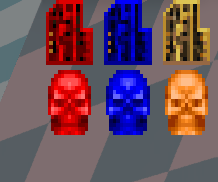

The flags can be combined using | to define both corner and edge offsets, e.g. DI_SCREEN_LEFT|DI_SCREEN_TOP. However, there are also pre-combined flags available, which are more commonly used (such as DI_SCREEN_LEFT_TOP); here’s how they’re positioned on the screen:

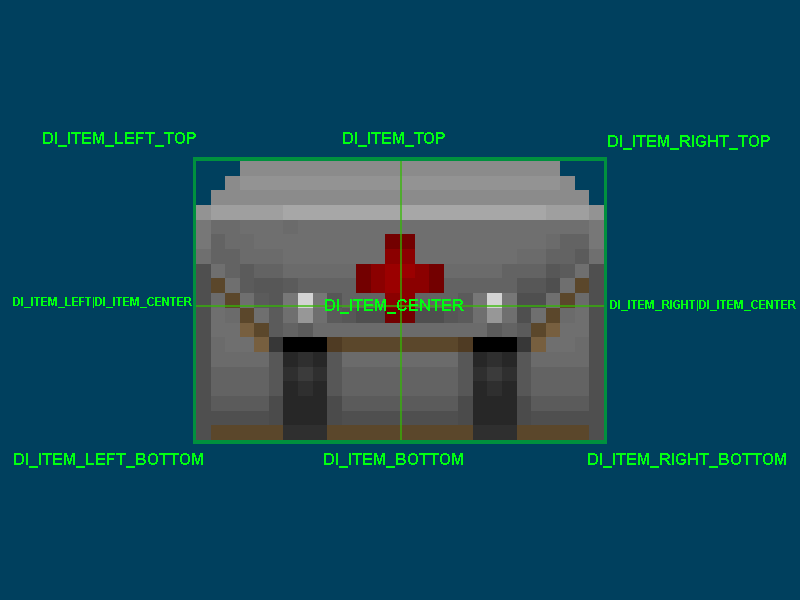

DI_ITEM* flags define where the HUD graphic itself will be placed relative to the specified coordinates. For example, with DI_ITEM_LEFT_TOP the anchor point will be placed at the top left corner of the image. Note, that the graphic’s own offsets are ignored when drawn on the HUD, instead the DI_ITEM* flags define its relative position. This allows you to draw graphics on the screen, such as sprites, without worrying about their initial offsets.

Similarly to DI_SCREEN* flags, DI_ITEM* flags can be combined, but there are also some combinatory flags already available. Here’s how they define anchor points of an element:

Combining DI_SCREEN* and DI_ITEM* flags, you can position graphics relative to screen corners, edges or center without worrying about the size of the image, or the screen. For example, let’s say we want to draw a medikit sprite at the center of the screen:

DrawImage("MEDIA0", (0,0), DI_SCREEN_CENTER);

Simply use | to append one of the DI_ITEM* flags, e.g.:

DrawImage("MEDIA0", (0,0), DI_SCREEN_CENTER|DI_ITEM_LEFT_TOP);

The GIF below demonstrates how the different DI_ITEM* flags will move the image relative to its origin point (the origin is marked with a red circle):

To reiterate:

-

The offsets (

(0, 0)in this example) and theDI_SCREEN*flags define the position of the origin point. -

The

DI_ITEM*flags define the position of the image relative to the specified origin point.

Using this knowledge, you can draw an image at the top left corner:

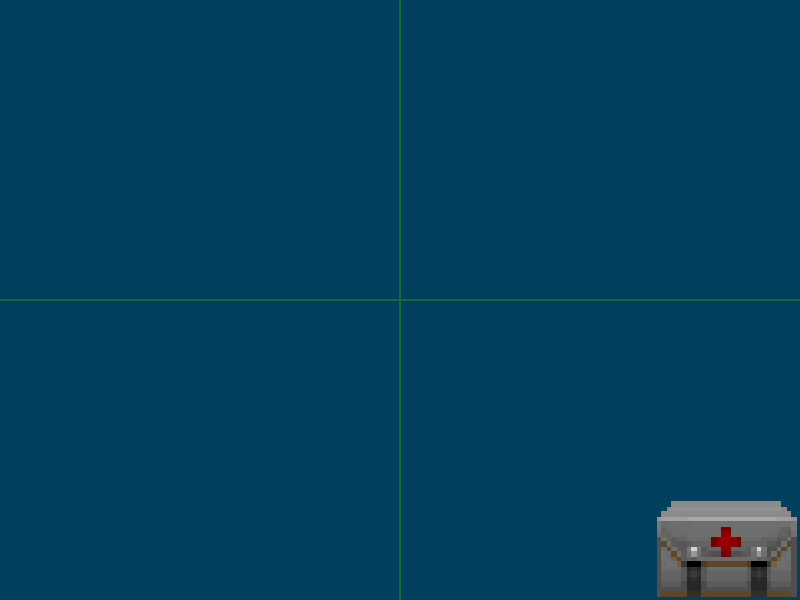

DrawImage("MEDIA0", (0,0), DI_SCREEN_LEFT_TOP|DI_ITEM_LEFT_TOP);

Conversely, if you need to place an element exactly at the left bottom corner and you don’t want to worry about the size of the image or screen resolution, use this:

DrawImage("MEDIA", (0,0), DI_SCREEN_LEFT_BOTTOM|DI_ITEM_LEFT_BOTTOM);

Note that in both cases we’re using (0, 0) as offsets, meaning the image is drawn directly adjacent to the screen edges/corners. You can use offsets to adjust its relative position. For example, this will draw the Medikit sprite at the bottom right corner, but 2 pixels away from the bottom and the right edges:

DrawImage("MEDIA", (-2,-2), DI_SCREEN_RIGHT_BOTTOM|DI_ITEM_RIGHT_BOTTOM);

Note that DrawImage() and most of the other drawing functions support their own scaling, sepate from the HUD size. For example, you can have a 320x200 HUD but draw the Medikit twice as large:

DrawImage("MEDIA", (-2,-2), DI_SCREEN_RIGHT_BOTTOM|DI_ITEM_RIGHT_BOTTOM, scale: (2, 2));

As long as the flags are set up correctly, the image will remain at the same place but will change its size.

Note, scaling of a specific HUD element is unrelated to the HUD’s own scale, which can be controlled by the user (explained below).

Text offsets

If you’re drawing text or numbers, e.g. with DrawString(), DI_ITEM* flags are not applicable. Instead you’ll need DI_TEXT* flags.

The principle is the same, except the only flags are DI_TEXT_ALIGN_LEFT, DI_TEXT_ALIGN_RIGHT and DI_TEXT_ALIGN_CENTER. By using them you’ll define where the text is placed on the screen. For example:

DrawString(mIndexFont, CPlayer.health, (0, 64), DI_SCREEN_CENTER|DI_TEXT_ALIGN_CENTER);

This will draw the player’s current health 64 units under the center of the screen, with the text aligned to the center.

HUD scaling

By default the player can control the scale of their hud by using the -/= keyboard keys or the “User interface scale” menu option (found under Options > HUD Options > Scaling Options).

For statusbar HUDs, the whole HUD area will be changed in size, and the elements in it will change their size with it.

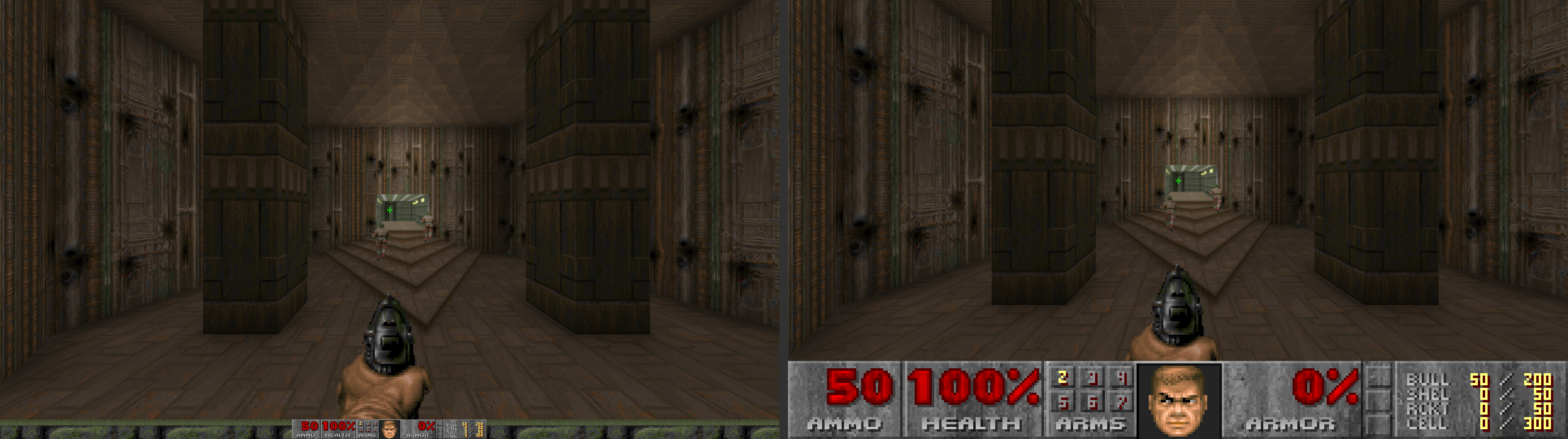

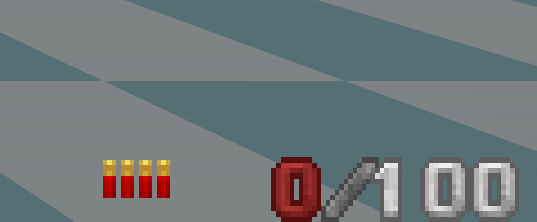

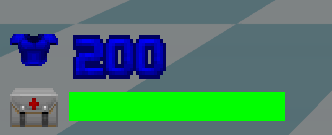

Left: x1UI scale. Right: x4 UI scale.

Since normally statusbars only include a single bar graphic at the bottom, it may seem like only that graphic changes. But in fact, the whole previously allocated area changes (relative to the bottom center of the screen), so if you put anything above the statusbar, it’ll be moved as well.

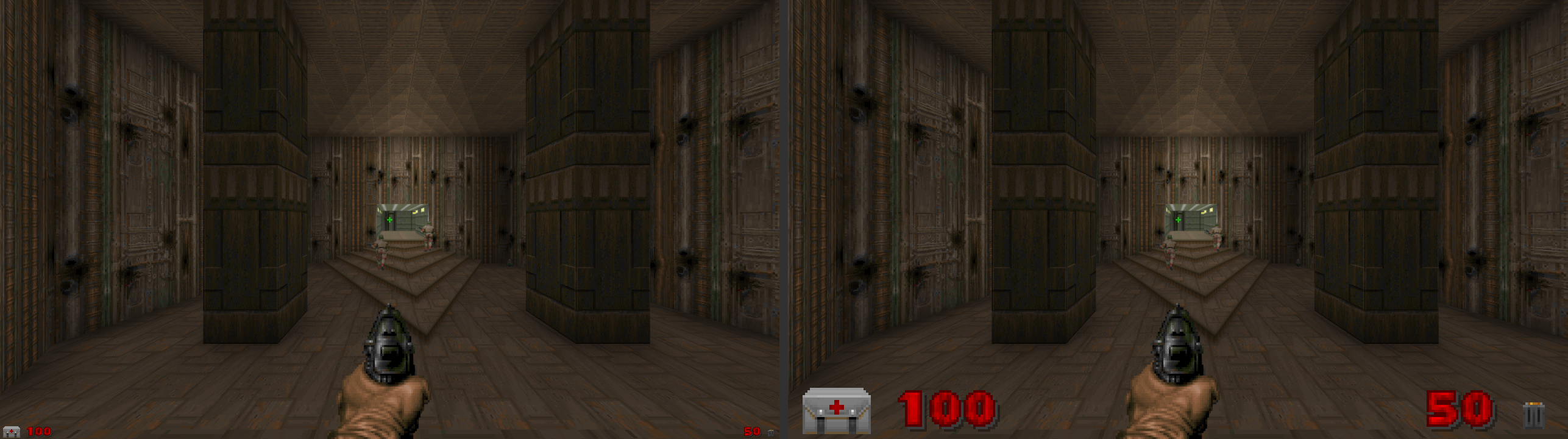

For fullscreen HUDs, however, things are different. The area of a fullscreen HUD is always the whole screen and that fact doesnt change with the scaling. Instead, the visual size and position of every element is changed:

Left: x1UI scale. Right: x4 UI scale. Note how the health and ammo indicators remain in the corners regardless of scale settings. Changing the resolution to a different aspect ratio will also not affect their placement.

As such, if you want to incorporate scaling properly, you once again must use the DI_SCREEN and DI_ITEM flags mentioned earlier, so that the elements of your HUD remain in the same relative places despite changing their size. As shown earlier, if you want to draw a Medikit sprite at the bottom left corner, use this:

DrawImage("MEDIA", (0,0), DI_SCREEN_LEFT_BOTTOM|DI_ITEM_LEFT_BOTTOM);

With this the graphic will remain at the bottom left corner, regardless of UI scale.

However, if you define a 320x200 HUD and then try to achieve the same with explicit offsets like this:

DrawImage("MEDIA", (0,292));

…this will break immediately when the player decides to use non-default UI scale, since the 292 position will be moved around relative to the scaling options. That’s why using DI_SCREEN* and DI_ITEM* flags, as described in the previous section, is so important.

It is also possible to disable the option to scale the HUD completely by setting the forceScaled argument of the BeginHUD() and/or BeginStatusBar() to true, however, this basically robs the user of a feature they may find useful without a good reason, so I do not recommend doing that.

HUD aspect ratio

As you might know, all of Doom graphics is vertically stretched by the factor of 1.2. HUDs are not an exception: they are also vertically stretched by default. At the moment of writing this, the only way to disable that behavior for HUDs is to set the forceScaled argument of the BeginHUD() and/or BeginStatusBar() to true, however that also disables the ability for the user to change the size of the HUD, which is usually undesirable.

HUD aspect ratio is controlled by the hud_aspectscale console command: when set to true (default), the HUD graphics will be stretched.

Most of the time you don’t need to worry about this, unles your HUD features circular elements, because those will be stretched or squished when the user switched to the other aspect ratio than the one the images were authored for.

Drawing in the HUD

Finally, let’s talk about how to draw things!

Setting up a font

If you’re planning to draw text or numbers anywhere in the HUD, you’ll first need to set up a HUD font. Fonts used by the HUD have to be cached to a field of the HUDFont type and created with the HUDFont.Create() function. But before that they also need to be obtained and cast to a Font-type variable.

This is normally done only once, in Init():

class MyHUD : BaseStatusBar

{

// This will contain a reference to the font:

HUDFont mIndexFont;

override void Init()

{

super.Init();

Font fnt = "Indexfont"; //obtain the font named "Indexfont"

mIndexFont = HUDFont.Create(fnt); //create the font and cache it to mIndexFont

}

}

After this point you’ll be able to use mIndexFont in functions like DrawString(). Note, the variable name, as usual, can be anything; I’m using mIndexFont as an example, since this is what is used in DoomStatusBar.

I should note that HUDFont is a whole separate class, whose purpose is to handle HUD fonts, and Create() is its only method. Among other things, Create() allows specifying monospaced fonts or defining custom spacing. The full list of arguments of this method goes like this:

HUDFont.Create(Font fnt, int spacing = 0, bool monospaced = false, int shadowx = 0, int shadowy = 0)

You can find the documentation for this class on ZDoom Wiki.

DrawImage()

native void DrawImage(String texture, Vector2 pos, int flags = 0, double Alpha = 1., Vector2 box = (-1, -1), Vector2 scale = (1, 1));

As you can see by the native keyword, this function is defined in C++. The arguments work as follows:

-

string texture— the name of the texture. Despite being defined as astring, all graphic names are case-insensitive. Although the word “texture” is used, you can actually use any image here: textures, flats, graphics or sprites. -

vector2 pos— the position where the element will be drawn. See notes on the offsets above to learn how the position works with various offsets. Note that the graphic’s offsets set via SLADE are ignored and do not affect its placement. -

int flags— a bit field for flags, such asDI_SCREEN*andDI_ITEM*flags. -

double alpha— the translucency of the element, from 0.0 to 1.0. -

vector2 box— allows defining a fixed-size area, and if the image’s pixel dimensions are higher than it, it’ll be automatically scaled to fit within that box. For example, if you use a 48x32 image but define the box argument as(12, 12), the image will be scaled to fit 12x12 square (while still keeping its original aspect ratio). The default value is(-1, -1), which means the box’s size will be equal to the size of the image. -

vector2 scale— the individual scale of the element (independent from the general HUD scale); works pretty much like, for example, actor scale. Note, this is relative scale, e.g. at(2, 2)the element will appear x2 larger than it normally would.

DrawTexture()

void DrawTexture(TextureID texture, Vector2 pos, int flags = 0, double Alpha = 1., Vector2 box = (-1, -1), Vector2 scale = (1, 1))

This function is largely identical to DrawImage(), with the exception of the first argument: instead of taking the name of a graphic as a string, it takes a TextureID-type argument. TextureID is a special data type that contains a reference to a texture, but not the actual texture name. TextureID can be obtained with the following syntax:

TextureID tex = TexMan.CheckForTexture("BAL1A0"); // get a textureID for BAL1A0, the Imp's fireball graphic

The management of TextureID data type is relegated to a dedicated struct, TexMan (the name stands for “texture manager”). This struct contains methods to obtain a TextureID (CheckForTexture()), obtain a name of a texture for a given TextureID (GetName()), getting its size (GetScaledSize()) and others.

At the same time, TextureID is also a separate struct which defines methods for checking if an obtained texture is valid and existing. Primarily you will be using IsValid() to check that the TextureID you obtained is valid. IsValid() in that sense is an analog of != null for class instances. E.g.:

TextureID tex = TexMan.CheckForTexture("MYTEX");

// Only draw the texture if it's a valid texture:

if (tex.IsValid())

{

DrawTexture(tex, (0, 0), DI_SCREEN_CENTER|DI_ITEM_CENTER);

}

DrawString()

void DrawString(HUDFont font, String string, Vector2 pos, int flags = 0, int translation = Font.CR_UNTRANSLATED, double Alpha = 1., int wrapwidth = -1, int linespacing = 4, Vector2 scale = (1, 1))

This function draws a string of text. Note, it needs a HUDFont font to be set up before it can be used. The argumenst are:

-

HUDFont font— pointer to a HUDFont instances you’ve created earlier withHUDFont.Create(). -

String string— the actual text to be displayed. Instead of writing the text literally, if you’re using the LANGUAGE lump, you can passStringTable.Localize("$LANGUAGECODE")to display the correct string as defined in LANGUAGE. You can also use various String methods, such asString.Format()to format your string with numeric variables, color codes, etc. -

Vector2 pos— the position of the text element, just like inDrawImage(). -

int flags— a bit field for flags, such asDI_TEXT_ALIGN_LEFT,DI_TEXT_ALIGN_RIGHTandDI_TEXT_ALIGN_CENTER(determine how the text will be aligned relative to the specified position), as well as the DI_SCREEN* flags mentioned earlier. -

int translation— the color translation applied to the font. Note, this isn’t a traditional color translation defined in the TRNSLATE lump, but rather a specific Font color code, for exampleFont.CR_Red,Font.CR_White, etc. The default value,Font.CR_UNTRANSLATED, means the color of the font graphics will be used as is. -

double alpha— the translucency of the element, from 0.0 to 1.0. -

int wrapwidth— defines the length of the string in pixels at which it should wrap and start a new line. The default value is-1which disables wrapping. -

int linespacing— defines the spacing between lines if the text is wrapped. -

vector2 scale— the individual scale of the element (independent from the general HUD scale). Can be used to make the text appear larger or smaller relative to the size of its glyphs.

DrawInventoryIcon()

void DrawInventoryIcon(Inventory item, Vector2 pos, int flags = 0, double alpha = 1.0, Vector2 boxsize = (-1, -1), Vector2 scale = (1.,1.))

This function is largely similar to DrawImage() but instead it takes a pointer to a specific Inventory class instance and obtains its icon. If the icon can’t be found, it’ll automatically try to obtain its Spawn state sprite, and it can optionally read Ready or Fire state sprites (which can be used for weapons), e.g.:

let arm = CPlayer.mo.FindInventory("BasicArmor"); //a pointer to the class that handles armor

if (arm)

{

DrawInventoryIcon(it, (0, 0), DI_SCREEN_RIGHT_BOTTOM|DI_ITEM_RIGHT_BOTTOM);

}

Information functions

BaseStatusBar defines many functions that can be used to retrieve various information. Some of them are:

-

int GetArmorAmount()— returns the current amount of armor the player has. -

int GetArmorSavePercent()— returns the armor’ssavepercentvalue (damage absorption). -

String GetWeaponTag()— returns the select weapon’sTagproperty as a string (usually contains the weapon’s name). -

bool isInvulnerable()— returnstrueif the player is currently invulnerable due to power-ups or other effects.

These are just some of the examples, but many more can be found on ZDoom Wiki.

Force 1:1 aspect ratio without disabling UI scaling

If you’re determined to create a HUD that supports UI scaling, yet looks identical regardless of aspect ratio, it’s actually possible. You will have to check the value of the hud_aspectscale CVar and then divide Y position and Y size of all elements by 1.2 in order to counter aspect ratio changes. This can be achieved with a wrapper function. For example, for DrawImage() it’d look like this:

// As with all constants, this constant can be

// defined anywhere. It matches the default aspect

// correction value, which is 1.2:

const ASPECTBLOCK = 1.2;

// This wrapper function works just like DrawImage,

// except images drawn with it will always look as if

// 1:1 aspect ratio is used. It uses exactly the same

// arguments as the regular DrawImage():

void NoAspectDrawImage(String texture, Vector2 pos, int flags = 0, double Alpha = 1., Vector2 box = (-1, -1), Vector2 scale = (1, 1))

{

// Check the value of the CVar (since it's a nosave CVar,

// we can check its value directly, without CVar.GetCVar):

if (hud_aspectscale == true)

{

// If it's true, modify vertical scale and position

// so it counteracts aspect scaling:

scale.y /= ASPECTBLOCK;

pos.y /= ASPECTBLOCK;

}

// Use the final values to draw the actual image:

DrawImage(texture, pos, flags, Alpha, box, scale);

}

Making your first HUD from A to Z

Now, armed with all the knowledge above, let’s make your first HUD! This section will cover the process step by step. The code for the whole HUD will be available with this guide, and you can find it here.

We’ll focus on making a fullscreen HUD that contains all vital information and generally behaves similar to GZDoom’s built-in fullscreen HUD. The HUD we’ll make will display the following:

-

Health and armor (with icons and colorized numbers)

-

Selected weapon’s ammo (with icons and colorized numbers)

-

Possessed keys (in several rows/columns)

-

All possessed ammo (not just for the selected weapon)

Let’s start simple. First, we’ll create a sample project with the following file and folder structure:

zscript.zs

MAPINFO.txt

MyScripts/

hud.zs

In zscript.zs add:

version "4.14.0" //use your target minimum GZDoom version

#include "MyScripts/hud.zs"

In MAPINFO.txt add:

GameInfo

{

StatusBarClass = "MyFullscreenHUD"

}

Finally, go to the MyScripts folder and in hud.zs add an empty HUD:

class MyFullscreenHUD : BaseStatusBar

{

override void Draw(int state, double TicFrac)

{

// Start with a super call:

Super.Draw(state, TicFrac);

// Don't draw anything if the HUD is disabled,

// or if the Alternative HUD is used:

if (state == HUD_None || state == HUD_AltHUD)

{

return;

}

// This is required before we can draw anything:

BeginHUD();

// We'll add our custom stuff here later.

}

}

You can test this now: this HUD shows nothing because it doesn’t call any drawing functions.

Note: for readability and to make sure we don’t overlap with any variables or functions that are already defined in BaseStatusBar, we’ll be prefixing all of our variables and functions with my_ (you can use a different custom prefix, of course).

Defining fonts to use in your HUD

First, we need to add a font, because we will, of course, need to draw things in the HUD. Doom comes with several fonts: SmallFont, NewSmallFont, ConsoleFont, NewConsoleFont and BigFont. Doom also supports BigUpper, which is a version of the classic Doom font that also supports lowercase letters (vanilla big font is uppercase-only). We’ll be using BigFont here, so let’s start by creating a HUDFont for BigFont.

To do this, we will need to define a new HUDFont-type field in our HUD, and then create a HUDFont object and store it in that field in the HUD’s Init().

In addition to that, we will have a separate double-type field which will store the font’s height. We’ll use it later to make sure icons placed next to text match its size, so trust me on this. Let’s go:

class MyFullscreenHUD : BaseStatusBar

{

HUDFont my_BigFont; // This will contain our hud font

double my_BigFontHeight; // This will contain the font's height

// This virtual is called once, when the HUD is

// initalized:

override void Init()

{

// Start with a super call, as usual:

Super.Init();

// Get a Font object for the font we

// want to use:

Font f = Font.FindFont('BigFont');

// Now convert it into a HUDFont object,

// which is a font that can be specifically

// used in HUDs:

if (f)

{

my_BigFont = HUDFont.Create(f); // Create a hud font

my_BigFontHeight = f.GetHeight(); // Store our font's height into a separate field

}

}

override void Draw(int state, double TicFrac)

{

Super.Draw(state, TicFrac);

// Don't draw anything if the HUD is disabled,

// or if the Alternative HUD is used:

if (state == HUD_None || state == HUD_AltHUD)

{

return;

}

BeginHUD();

// We'll add our custom stuff here later.

}

}

Great, now we have a font that can be used by the DrawString() function—we’ll just pass my_BigFont to it to draw text.

Drawing health and armor indicators

Now we’ll want to create a health and armor indicator. It’ll consist of 4 elements: two icons (one for armor, one for health) and two numbers.

We’ll add a separate function for each of our elements, so in this case we’ll create a function named My_DrawHealthArmor. To make it flexible, we’ll define a position argument and a flags argument in it, and we’ll pass those to each of the elements.

Let’s begin. Define this function anywhere inside your MyFullscreenHUD class:

void My_DrawHealthArmor(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{ }

And we’ll also add it to the Draw() override. For now, we’ll pass (0, 0) for position and DI_SCREEN_LEFT_BOTTOM to its arguments: we will want the elements to be drawn in the bottom left corner. Our HUD should look like this now:

class MyFullscreenHUD : BaseStatusBar

{

HUDFont my_BigFont;

double my_BigFontHeight;

override void Init()

{

Super.Init();

// Make font:

Font f = Font.FindFont('BigFont');

if (f)

{

my_BigFont = HUDFont.Create(f);

my_BigFontHeight = f.GetHeight();

}

}

override void Draw(int state, double TicFrac)

{

Super.Draw(state, TicFrac);

if (state == HUD_None || state == HUD_AltHUD)

{

return;

}

BeginHUD();

My_DrawHealthArmor((0, 0), DI_SCREEN_LEFT_BOTTOM);

}

void My_DrawHealthArmor(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

// Does nothing (for now)

}

}

At this point we want to draw a medikit icon—it’ll serve as a health icon—and a number next to it. We’ll use DrawImage() to draw the icon, and DrawString() to draw the text.

But wait! How do we reconcile the size of the font with the size of the icon?

Don’t worry. Remember that my_BigFontHeight field we defined earlier? We will use that and DrawImage()’s box argument to make sure the icon is made to fit into a box of specific size.

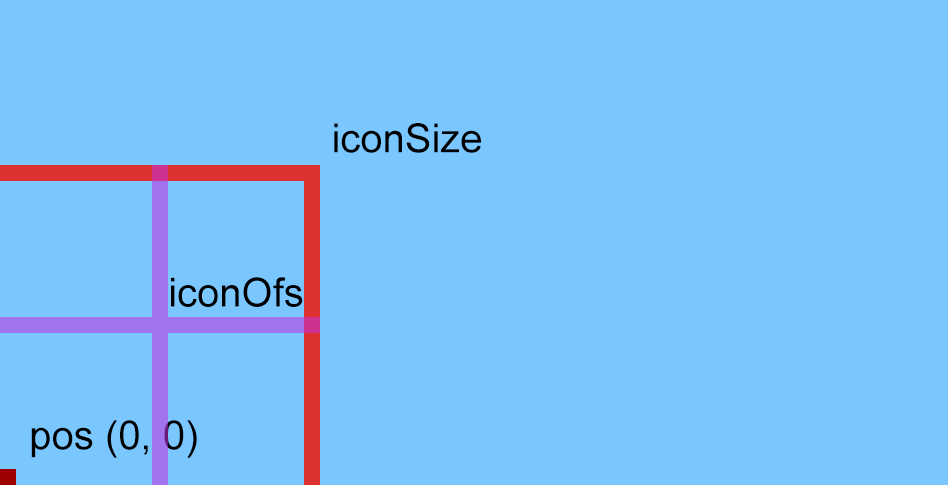

Let’s begin by defining the size of the box and the position of the icon:

void My_DrawHealthArmor(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

// Define a Vector2 that stores the maximum size

// of the health icon. This will be just font height X font height:

Vector2 iconSize = (my_BigFontHeight, my_BigFontHeight);

// Now, define the offsets from the base 'pos' at which

// the icon will be drawn. We will draw the icon anchored

// at its center, so its offsets will be half of its size:

Vector2 iconOfs = (iconSize.x * 0.5, iconSize.y * -0.5);

// ...

You might wonder why the Y component of iconOfs is defined as iconSize.y * -0.5. Why negative? Well, remember how the positions work in a HUD (or in UI in general): negative Y is up, positive Y is down. We are treating pos as the bottom left corner, and we’re offseting the icon and the text to the right and up from it. Hence the offsets for the icon use positive X (right) and negative Y (up).

Okay, let’s continue. Time to actually draw the icon:

void My_DrawHealthArmor(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

// Icon's target size (defined by font's height)

Vector2 iconSize = (my_BigFontHeight, my_BigFontHeight);

// Icon's offsets (50% of its width and height):

Vector2 iconOfs = (iconSize.x * 0.5, iconSize.y * -0.5);

DrawImage("MEDIA0", // Medikit icon

pos + iconOfs, // Base position plus icon offsets as defined above

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER, // Base flags plus anchor image at its center

box: iconSize // This will make sure the icon can't exceed given size

);

Since DrawImage() has a lot of arguments, I’m splitting it into multiple lines, and the result goes like this:

- “MEDIA0” is the Doom’s Medikit graphic we want to draw.

- The position at which the icon is drawn is defined as

pos + iconOfs.posis the base position, it’s obtained from the functions’sposargument.iconOfsis what we defined earlier: it’s 50% of theiconSizewidth and 50% of its height (negative, since we’re moving upwards). We’re using this, because we’ll anchor the icon at its center (see next point). - For

DrawImage()’s flags we’re usingflags|DI_ITEM_CENTER— this passes flags as defined in the function’sflagsargument (in the example above we’re passingDI_SCREEN_LEFT_BOTTOMthere), and also addingDI_ITEM_CENTERto them so that the icon gets anchored at its center. - Finally, we’re passing

iconSizeto the function’sboxargument to determine the max size of the icon. Note the syntax:box: iconSize. In case you forgot, this is called a named argument, and using this syntax we can pass the value to a specific argument (in this case the one calledbox), not worrying about the order of arguments, and not having to specify every single argument explicitly).

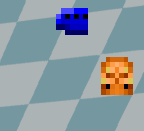

Here’s visualization of what we’re going for to help you get a better idea:

Before we move on, though, let’s go ahead and add one important detail that can easily get overlooked: the Berserk icon. Fullscreen HUDs made for Doom normally replace the Medikit icon with a Berserk Pack icon while the player has the Berserk Pack. This is a simple change: first, check if the player has a PowerStrength in their inventory (this is the Powerup that handles the actual Berserk effect), and if so, instead of “MEDIA0” we’ll draw “PSTRA0” (the Berserk sprite).

There are several ways we could structure this. For example:

String hpIconName = "MEDIA0";

if (CPlayer.mo.FindInventory('PowerStrength'))

{

hpIconName = "PSTRA0";

}

DrawImage(hpIconName,

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize

);

Or we could use a ternary operator inside the function itself:

DrawImage(CPlayer.mo.FindInventory('PowerStrength')? "PSTRA0" : "MEDIA0",

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize

);

Awesome, but now we need to also draw the text next to it. How do we position it?

The horizontal offset is easy: we’ll just use pos.x + iconSize.x so that the left side of the text begins at the right edge of the icon (you can optionally add a couple of pixels to it if you like). But the vertical positioning is a problem. Earlier in this chapter I said that the text drawn with DrawString() is always placed below the given position, but unfortunately, it’s not exactly like that. Fonts’ pixel size is a weird thing, where you can never exactly guess how the font is positioned, so usually it takes some eyeballing and guessing. For BigFont, which is what we’re using, 75% of its height roughly takes it to the center, so that’s what we’ll use:

void My_DrawHealthArmor(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

// Define a Vector2 that stores the maximum size

// of the health icon. This will be just font height X font height:

Vector2 iconSize = (my_BigFontHeight, my_BigFontHeight);

// Now, define the offsets from the base 'pos' at which

// the icon will be drawn. We will draw the icon anchored

// at its center, so its offsets will be half of its size:

Vector2 iconOfs = (iconSize.x * 0.5, iconSize.y * -0.5);

DrawImage(CPlayer.mo.FindInventory('PowerStrength')? "PSTRA0" : "MEDIA0",

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize

);

DrawString(my_BigFont, // Our BigFont HUDFont

String.Format("%d", CPlayer.health), // Conver player's health to string

pos + (iconSize.x, -my_BigFontHeight*0.75), // Add icon size to horizontal and 75% of font's height to vertical position

flags

);

}

Finally, let’s integrate all of it into our HUD. I said that we want to draw it at (0, 0) at the lower left corner of the screen, but after taking a look I decided it’s better to slightly offset it to the right, so we’ll use (4, 0) instead:

class MyFullscreenHUD : BaseStatusBar

{

HUDFont my_BigFont;

double my_BigFontHeight;

override void Init()

{

Super.Init();

// Make font:

Font f = Font.FindFont('BigFont');

if (f)

{

my_BigFont = HUDFont.Create(f);

my_BigFontHeight = f.GetHeight();

}

}

override void Draw(int state, double TicFrac)

{

Super.Draw(state, TicFrac);

if (state == HUD_None || state == HUD_AltHUD)

{

return;

}

BeginHUD();

// Draw health and armor:

My_DrawHealthArmor((4, 0), DI_SCREEN_LEFT_BOTTOM);

}

void My_DrawHealthArmor(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

// Icon size:

Vector2 iconSize = (my_BigFontHeight, my_BigFontHeight);

// Icon offsets:

Vector2 iconOfs = (iconSize.x * 0.5, iconSize.y * -0.5);

// Draw health/Berserk icon:

DrawImage(CPlayer.mo.FindInventory('PowerStrength')? "PSTRA0" : "MEDIA0",

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize

);

// Draw health text:

DrawString(my_BigFont,

String.Format("%d", CPlayer.health),

pos + (iconSize.x, -my_BigFontHeight*0.75),

flags

);

}

}

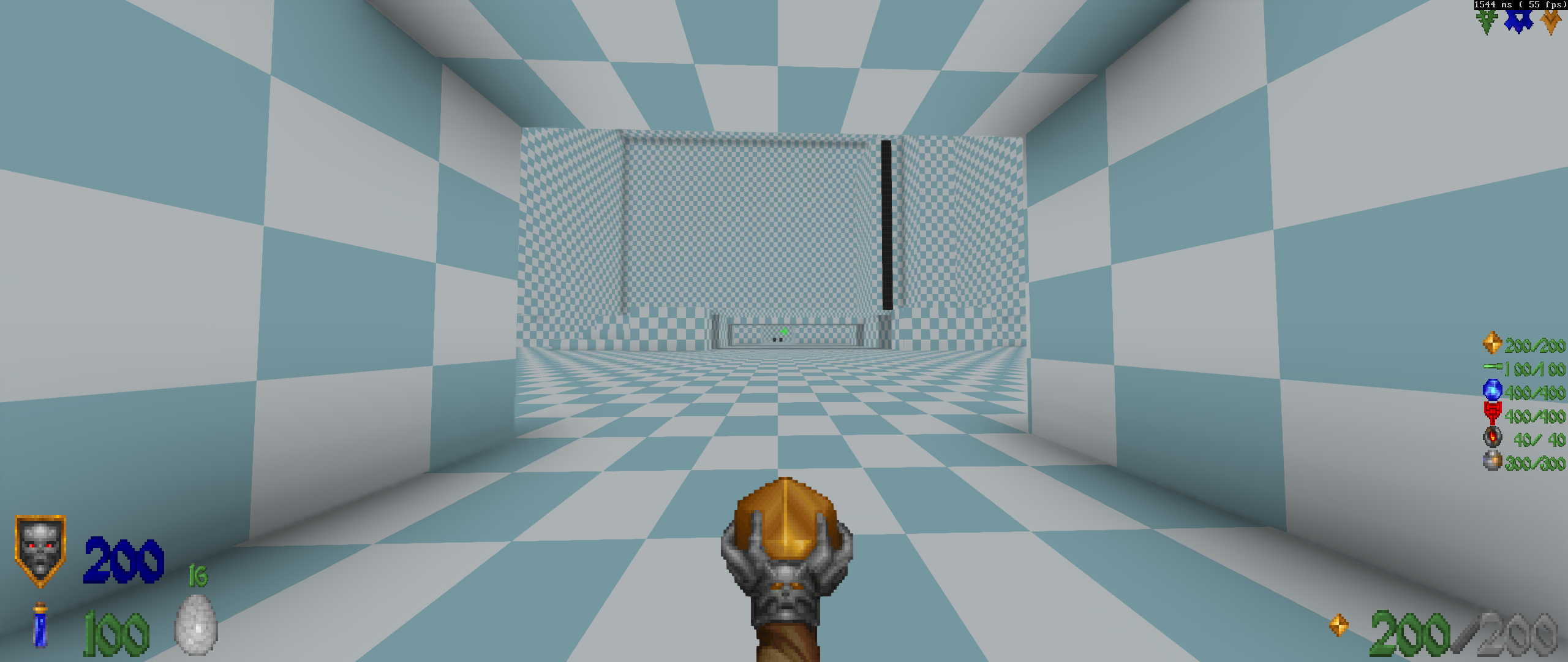

And with this we finally have a health display:

If you don’t like that the numbers are smooshed very close to the icon, just add some offsets to it:

DrawString(my_BigFont,

String.Format("%d", CPlayer.health),

pos + (iconSize.x + 4, -my_BigFontHeight*0.75), // horizontal offsets is icon's width + 4 pixels

flags

);

Great work! But now we need to draw armor.

We’ll use the same function and just draw an armor icon and value above it.

We’ll start by offsetting pos vertically because we want the icon to be drawn above health. Let’s offset it so it’s right above health, so we’ll use iconSize.y:

void My_DrawHealthArmor(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

// Icon size:

Vector2 iconSize = (my_BigFontHeight, my_BigFontHeight);

// Icon offsets:

Vector2 iconOfs = (iconSize.x * 0.5, iconSize.y * -0.5);

// Draw health/Berserk icon:

DrawImage(CPlayer.mo.FindInventory('PowerStrength')? "PSTRA0" : "MEDIA0",

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize

);

// Draw health text:

DrawString(my_BigFont,

String.Format("%d", CPlayer.health),

pos + (iconSize.x + 4, -my_BigFontHeight*0.75),

flags

);

pos.y -= iconSize.y; // Move the position up

//...

}

Don’t forget that to move up we use negative Y, hence -=, NOT +=.

Now, we’ll need to get the current armor’s icon. To do that you need to know how armor works in GZDoom, and it’s like this:

-

The player always has a BasicArmor item in their inventory, and it’s the one that handles the actual armor.

-

Whenever the player picks up an armor pickup or an armor bonus, those pickups modify that player’s BasicArmor: they change its icon and amount. After that the pickup is removed, and BasicArmor is now updated with the new armor.

Since we need to read the armor’s icon and amount, we’ll need to obtain a pointer to it:

// Find BasicArmor in player's inventory:

let armr = BasicArmor(CPlayer.mo.FindInventory('BasicArmor', true));

// If there's no armor (for some reason), or there is

// but its amount is 0, stop here and do nothing else:

if (!armr || armr.amount <= 0) return;

Note that we’re using BasicArmor(CPlayer.mo.FindInventory('BasicArmor', true)) — we’re looking for BasicArmor and items based on BasicArmor (using true for FindInventory()’s second argument lets it look for subclasses). This is important, because since GZDoom 4.13.0 it’s now possible to use custom BasicArmor versions, but they’ll still be based on the BasicArmor class, so we have to use subclass-sensitive search here.

After that we can use DrawTexture() to draw its icon, and DrawString() to draw its amount. Note: we’re using DrawTexture(), NOT DrawImage(), because any item’s icon is a TextureID, it’s an itnernal identifier of a texture, it’s not a name. In contrast, DrawImage() is a function that takes a graphic’s name and then internally converts it to a TextureID to draw it. Since icon is already a TextureID, we just draw it with DrawTexture() directly. Other than that, this block is more or less identical to what we used for health:

// Draw armor icon:

DrawTexture(armr.icon, //the current armor's icon

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize

);

// Draw armor text:

DrawString(my_BigFont,

String.Format("%d", armr.amount), //the current armor's amount

pos + (iconSize.x + 4, -my_BigFontHeight*0.75),

flags

);

And finally, let’s take a look at our HUD again:

class MyFullscreenHUD : BaseStatusBar

{

HUDFont my_BigFont;

double my_BigFontHeight;

override void Init()

{

Super.Init();

// Make font:

Font f = Font.FindFont('BigFont');

if (f)

{

my_BigFont = HUDFont.Create(f);

my_BigFontHeight = f.GetHeight();

}

}

override void Draw(int state, double TicFrac)

{

Super.Draw(state, TicFrac);

if (state == HUD_None || state == HUD_AltHUD)

{

return;

}

BeginHUD();

// Draw health and armor:

My_DrawHealthArmor((4, 0), DI_SCREEN_LEFT_BOTTOM);

}

void My_DrawHealthArmor(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

// Icon size:

Vector2 iconSize = (my_BigFontHeight, my_BigFontHeight);

// Icon offsets:

Vector2 iconOfs = (iconSize.x * 0.5, iconSize.y * -0.5);

// Draw health/Berserk icon:

DrawImage(CPlayer.mo.FindInventory('PowerStrength')? "PSTRA0" : "MEDIA0",

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize

);

// Draw health text:

DrawString(my_BigFont,

String.Format("%d", CPlayer.health),

pos + (iconSize.x + 4, -my_BigFontHeight*0.75),

flags

);

pos.y -= iconSize.y; // Move the base position up to draw armor

// Find BasicArmor in player's inventory:

let armr = BasicArmor(CPlayer.mo.FindInventory('BasicArmor', true));

// If there's no armor (for some reason), or there is

// but its amount is 0, stop here and do nothing else:

if (!armr || armr.amount <= 0) return;

// Draw armor icon:

DrawTexture(armr.icon,

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize

);

// Draw armor text:

DrawString(my_BigFont,

String.Format("%d", armr.amount),

pos + (iconSize.x + 4, -my_BigFontHeight*0.75),

flags

);

}

}

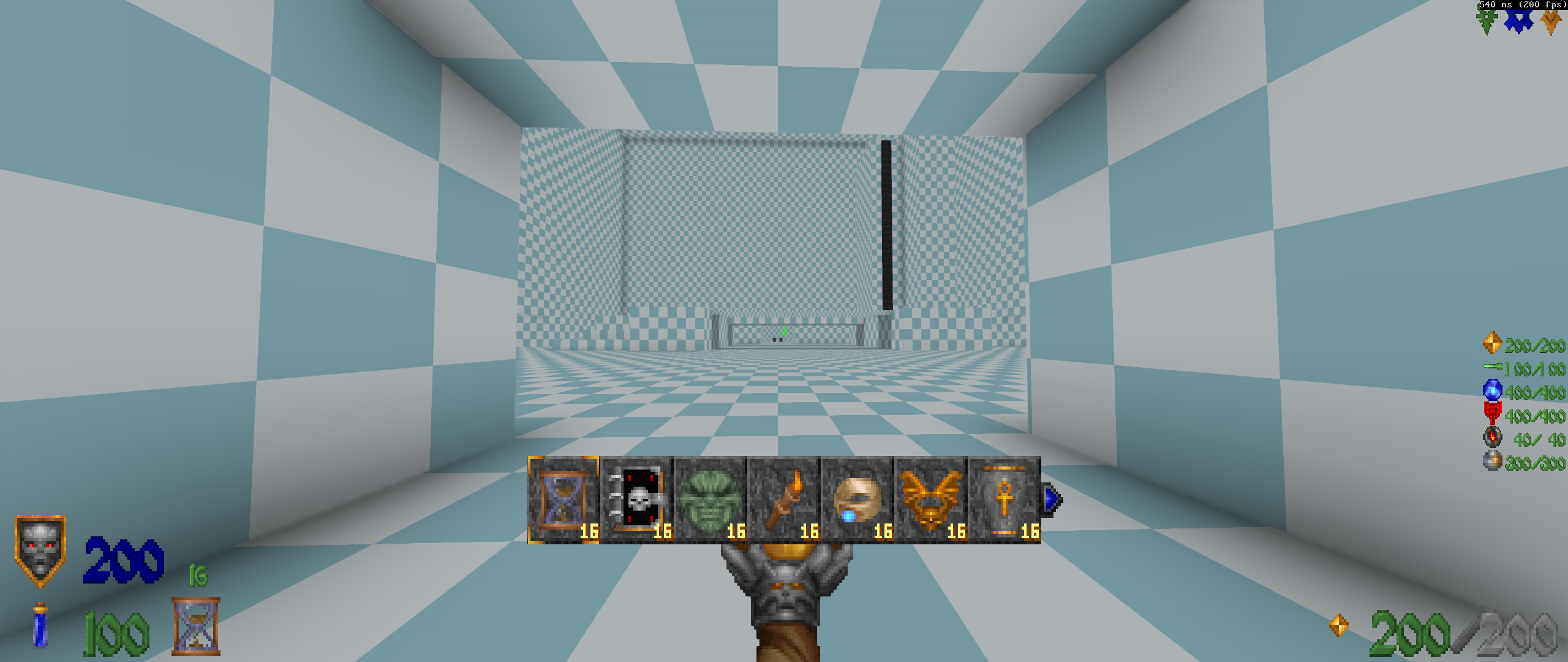

You can test it in the game by finding or giving yourself some armor (e.g. with the give all console cheat):

Colorizing health numbers

Usually health and armor numbers have colors. You can do that too: DrawString(), which we’re using to draw the numbers, has an int translation argument which determines the color of the string. Note, text colors are not actual Color-type values (which can be given in RRGGBB format), but rather an int value that is associated with dedicated constants, such as Font.CR_Red, Font.CR_White, and others (you can see the full list here on the wiki). By default the color is set to Font.CR_Untranslated, which just uses the font’s own color (and in case of the BigFont font that we’re using, it’s white).

So, how do we conditionally set that color?

Well, first, you will need to determine what logic you want to utilize, since usually it’s an explicit value. A common approach would look something like this:

-

20 HP or below — red;

-

21–50 — orange;

-

51–75 — yellow;

-

76–100 — green;

-

101 HP or above — blue (or cyan).

Obviously, you can choose different colors and a different amount of ranges, but we’ll use the above as an example. To handle health color conditions we’ll create a simple separate function that returns an int for our HUD:

int My_GetHealthColor(int health)

{

if (health <= 20)

{

return Font.CR_Red;

}

else if (health <= 50)

{

return Font.CR_Orange;

}

else if (health <= 75)

{

return Font.CR_Yellow;

}

else if (health <= 100)

{

return Font.CR_Green;

}

return Font.CR_Blue;

}

And now we’ll modify our My_DrawHealthArmor function to include the above function to get the color. The value of the function will be passed to DrawString()’s argument called translation—that’s the font color (the name itself is kind of a misnomer, since it’s not a traditional color translation).

void My_DrawHealthArmor(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

// Icon size:

Vector2 iconSize = (my_BigFontHeight, my_BigFontHeight);

// Icon offsets:

Vector2 iconOfs = (iconSize.x * 0.5, iconSize.y * -0.5);

// Draw health/Berserk icon:

DrawImage(CPlayer.mo.FindInventory('PowerStrength')? "PSTRA0" : "MEDIA0",

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize

);

// Draw health text:

DrawString(my_BigFont,

String.Format("%d", CPlayer.health),

pos + (iconSize.x + 4, -my_BigFontHeight*0.75),

flags,

translation: My_GetHealthColor(CPlayer.health) //get font color from our new function

);

// continue to draw armor as usual; omitted for brevity

Boot into the game, and you’ll see our health numbers are now colorized:

Colorizing armor numbers

Okay, what about armor, then? Well, the approach is very similar to health numbers, and technically, you could use the same ranges. However, in practice traditionally armor numbers are designed to reflect armor absorption rather than the amount of armor. You know how you can pick up blue armor and then, once you’re damaged enough, its amount may fall below 100, but it’s still a blue armor and offers higher absorption than green armor? Yeah, that’s absorption, which is a separate value from amount.

Armor’s absorption is stored in the BasicArmor’s savePercent value. This is a double value in the 0.0–1.0 range. Alternatively, BaseStatusBar also comes with a dedicated function, GetArmorSavePercent(), which returns an int value in the 0–100 range, which is the percentage; you can use whichever works for you.

For this example, we’ll be reading the savePercent field directly, because we’re already obtaining a pointer to BasicArmor in My_DrawHealthArmor(). This means, that now we’ll have to design a function that returns different font colors — much like My_GetHealthColor() we made earlier — but it’ll take a double value in a 0.0–1.0 range.

Now, the question is, what colors we use and at what values. Again, this is up to you, but it’s worth noting that Doom only comes with two armors: GreenArmor, which has a savepercent of 33.335, and BlueArmor, which has a savepercent of 50, so, those are the only two values worth checking for standard gameplay. As such, we could just do this:

int My_GetArmorColor(double savepercent)

{

// this will catch blue armor:

if (savepercent >= 0.5)

{

return Font.CR_Blue;

}

// this will catch the rest (green armor);

return Font.CR_Green;

}

But it might be worth extending it, if you want to account for gameplay mods which sometimes feature custom armors with custom savepercent values. So, perhaps it’s worth checking for a few more conditions, just in case:

int My_GetArmorColor(double savepercent)

{

if (savepercent >= 0.8) //80% or more (doesn't exist in vanilla Doom)

{

return Font.CR_Red;

}

else if (savepercent >= 0.5) //50% or more (blue armor)

{

return Font.CR_Blue;

}

// this will catch the rest (including green armor);

return Font.CR_Green;

}

Obviously, you can modify this to your needs. Now all we need is to modify our My_DrawHealthArmor() to include the above function into the part where we draw armor numbers. The whole function will now look like this (incorporating colorized health and armor numbers):

void My_DrawHealthArmor(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

// Icon size:

Vector2 iconSize = (my_BigFontHeight, my_BigFontHeight);

// Icon offsets:

Vector2 iconOfs = (iconSize.x * 0.5, iconSize.y * -0.5);

// Draw health/Berserk icon:

DrawImage(CPlayer.mo.FindInventory('PowerStrength')? "PSTRA0" : "MEDIA0",

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize

);

// Draw health text:

DrawString(my_BigFont,

String.Format("%d", CPlayer.health),

pos + (iconSize.x + 4, -my_BigFontHeight*0.75),

flags,

translation: My_GetHealthColor(CPlayer.health) //colorize health numbers

);

pos.y -= iconSize.y;

// Find BasicArmor in player's inventory:

let armr = BasicArmor(CPlayer.mo.FindInventory('BasicArmor', true));

// If there's no armor (for some reason), or there is

// but its amount is 0, stop here and do nothing else:

if (!armr || armr.amount <= 0) return;

// Draw armor icon:

DrawTexture(armr.icon,

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize

);

// Draw armor text:

DrawString(my_BigFont,

String.Format("%d", armr.amount),

pos + (iconSize.x + 4, -my_BigFontHeight*0.75),

flags,

translation: My_GetArmorColor(armr.savepercent) //colorize armor numbers

);

}

And here we go (full health and Blue Armor):

Drawing current ammo and weapon

Now that we’re finally done with health and armor display, we need to draw current ammo. This will be a separate element, and we’ll draw it traditionally, in the bottom right corner of our HUD. Just like with My_DrawHealthArmor(), this will its own separate function:

void My_DrawCurrentAmmo(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

}

Now, the question is, what do we actually draw here? Obviously, current ammo, but there are many things we could draw:

-

Ammo 1 amount for the current weapon

-

Ammo 2 amount for the current weapon (many mods use multiple ammo types, and some vanilla games too, like Hexen)

-

Ammo 1 icon

-

Ammo 2 icon

-

Maximum ammo amounts (for example, instead of just “25” we could display it as “25 / 100” (25 out of 100) for each ammo type.

-

Optionally, the current weapon’s icon.

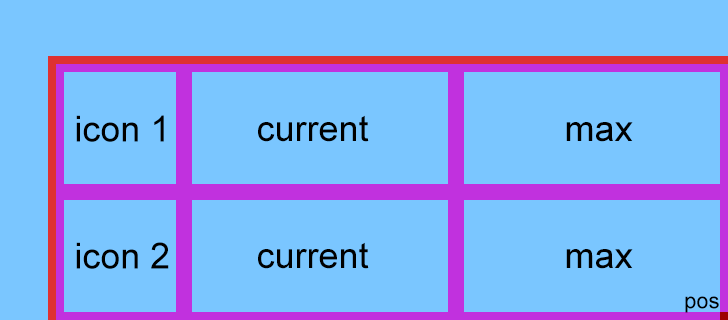

For this example we’ll skip the weapon icon, but we will draw both ammo types in the current / max format, and we’ll draw their icons, too. This means, we’ll need to draw 6 elements.

Since we’re going to draw this element in the bottom right corner, our offsets will need to move right-to-left and upward—this means that both X and Y will be negative relative to the base pos.

The order of operations will also be slightly different. We’ll be starting at the bottom-right corner of the element, but the things we draw will still need to be drawn left-to-right: icon, current amount, max amount. What’s more, for cases when the weapon has two ammo types, we’ll need to draw ammo 1 first, with ammo 2 below (in contrast to how we did health and armor, where health was below armor). As a result, we’ll need to perform a number of pre-calculations here.

Our first step is getting pointers to the Ammo items used by the current weapon, and their amounts. BaseStatusBar has a dedicated function that does this — GetCurrentAmmo() — which returns 4 values: pointer to ammo 1, pointer to ammo 2, amount of ammo 1, amount of ammo 2.

So, we’ll start with this:

void My_DrawCurrentAmmo(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

let [am1, am2, am1amt, am2amt] = GetCurrentAmmo();

// Stop here if there's no current ammo

// (which means we either don't have a weapon,

// or the weapon uses no ammo):

if (!am1 && !am2) return;

// our actual code will be added here

}

Now that we have the beginning, we’ll calculate the maximum ammo icon size and icon offsets just like we did with My_DrawHealthArmor(), basing it on BigFont’s font height:

// Icon size and offsets:

Vector2 iconSize = (my_BigFontHeight, my_BigFontHeight);

Next, we need to move our position to the left and up to start drawing. The question is: by how much?

Well, first, let’s figure out our mental template. It should look something like this:

pos is where we start, and we’re going to move up and left to figure out the starting point for our draw calls.

The vertical height is easy: it’s just going to be equal to two heights of the icon (or two heights of the font, which is the same thing, as we’ve calculated). The horizontal distance is going to be more difficult, though.

By far the simplest option is to just specify some kind of an explicit offset. And we can, of course, just do that, by basically guessing values that look okay. Let’s add an offset of 128 units (negative, since we’re going to the left of pos), and see how it looks:

void My_DrawCurrentAmmo(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

let [am1, am2, am1amt, am2amt] = GetCurrentAmmo();

// Stop here if there's no current ammo

// (which means we either don't have a weapon,

// or the weapon uses no ammo):

if (!am1 && !am2) return;

// Icon size and offsets:

Vector2 iconSize = (my_BigFontHeight, my_BigFontHeight);

// Offsets are positive on X and Y, since we're

// now moving right and down:

Vector2 iconOfs = (iconSize.x * 0.5, iconSize.y * 0.5);

// Move left and up from the base position:

pos -= (128, iconSize.y*2);

// From here on, we're going to be moving right

// and down, so the offsets will be directed that way.

// Check if ammo 1 is valid:

if (am1)

{

// Draw an icon:

DrawTexture(am1.icon,

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize);

// Draw the amounts, reading values

// off the am1 pointer:

DrawString(my_BigFont,

String.Format("%d / %d", am1amt, am1.maxamount),

// Offset the text horizontally by the icon's width,

// and vertically by 25% of the height:

pos + (iconsize.x, my_BigFontHeight*0.25),

flags);

}

// Move down:

pos.y += iconSize.y;

// Draw ammo 2's icon and text the same way:

if (am2)

{

DrawTexture(am2.icon,

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize);

DrawString(my_BigFont,

String.Format("%d / %d", am2amt, am2.maxamount),

pos + (iconsize.x, my_BigFontHeight*0.25),

flags);

}

}

Now just make sure this function is called in our Draw() override, of course:

override void Draw(int state, double TicFrac)

{

Super.Draw(state, TicFrac);

if (state == HUD_None || state == HUD_AltHUD)

{

return;

}

BeginHUD();

// Draw health and armor:

My_DrawHealthArmor((4, 0), DI_SCREEN_LEFT_BOTTOM);

// Draw current ammo:

My_DrawCurrentAmmo((-4, 0), DI_SCREEN_RIGHT_BOTTOM);

}

…and lets test it in the game (I’m using an example dummy weapon which uses two ammo types for demonstrative purposes):

It works, but objectively it’s not great. Here are some things to consider:

-

the

/character doesn’t align between two strings, which doesn’t look that great; -

if the maximum amount of ammo is a 4-number figure (which is totally possible in gameplay mods), these numbers aren’t gonna fit.

So, we’re now going to use something a little more complex. Here are the steps we’ll need to take:

-

Find which of the current ammo types (if there are two) has the biggest maximum amount.

-

Get the numeric length of that max amount (for example, if it’s 600, its length will be 3).

-

We’ll pad each ammo string with spaces using that length, so that they both have the same size — this will line them up horizontally.

-

We’ll also calculate the pixel width of that “current / max” string, and use that pixel width to offset the starting point from

pos.

But there’s a problem: the font we set up is not monospaced, i.e. each character in that font has a different width. This makes string pixel width calculations imprecise, and makes it difficult to align things together. So, our first step here will be to make another version of the font, this time monospaced. We’ll need to declare another HUDFont-type field and create a separate HUDFont version of the BigFont font:

class MyFullscreenHUD : BaseStatusBar

{

HUDFont my_BigFont;

double my_BigFontHeight;

HUDFont my_BigFontMono; //monospaced version of BigFont

override void Init()

{

Super.Init();

// Make font:

Font f = Font.FindFont('BigFont');

if (f)

{

// Create normal version:

my_BigFont = HUDFont.Create(f);

my_BigFontHeight = f.GetHeight();

// Now create monospaced version, where every

// character has the same width as the "0" character:

my_BigFontMono = HUDFont.Create(f, f.GetCharWidth("0"), Mono_CellLeft);

}

}

// the rest of the HUD code as usual

Now we can continue. We’ve already calculated iconSize and iconOfs. Next step:

// Find out which of the current ammo types has the

// biggest maximum amount:

int biggestAmt = max (am1? am1.maxamount : 0, am2? am2.maxamount : 0);

// Now construct a dummy string using that max amount

// representing the structure of our final "current / max"

// string:

String dummyString = String.Format("%d/%d", biggestAmt, biggestAmt);

// And get the pixel width of that string with BigFont:

int ammoStringWidth = my_BigFontMono.mFont.GetCharWidth("0") * dummyString.Length();

You might be wondering about GetCharWidth(). This is a Font method that gets the pixel width of a given character. Since we defined this monospaced font to use the width of “0” as the base, we will get the width of the same character. One note though: this is a Font function, not a HUDFont function, so it can’t be called on a HUDFont object directly. But this isn’t a problem, because every HUDFont object has an mFont field which actually contains the Font object it was created from. Hence, my_BigFontMono.mFont gives us access to the font object, and we can call GetCharWidth() on it, to get the pixel width of the desired character in the BigFont font.

So, we get the maximum amount of the currently selected ammo (let’s assume it’s 600), construct a dummy string (in this example, “600/600”) and get its pixel width.

Now we shift the horizontal position of the coordinates leftward by a combined width of the icon and the pixel width of the string:

pos.x -= ammoStringWidth + iconSize.x;

Now we need to shift the vertical position up. By how much? Well, that’s simple: we already checked if the current weapon is using ammo at all, now we need to check which ones. A weapon may use either only ammo 1, or only ammo 2, or both, so we’ll perform a quick calculation:

int ammoTypes;

if (am1) ammoTypes++;

if (am2) ammoTypes++;

And we’ll shift the vertical position up by the vertical size of the icon multiplied by the number of types:

pos.y -= iconSize.y * ammoTypes;

One advantage of this method is, for example, if you’re going to make a very custom weapon mod where your weapons may have more than 2 ammo types, you’ll be able to easily extend this code and add any number here.

Now, don’t forget, we’ll also need to pad the string with spaces. We calculated the longest ammo amount earlier — biggestAmt — and we’ll need to pad every ammo amount string to that length. For example, if the longest amount is 600, we’ll want all displayed amounts to be padded to 3, so for example 45 will become ` 45, and so on. So, calculate that padding by converting biggestAmt to a string and calling Length()` on it:

int padding = String.Format("%d", biggestAmt).Length();

At this point you might need to learn how padding works, if you don’t know yet. For that, take a look at this section of the wiki page on String methods. Basically, String.Format allows you to pad strings with spaces to a given length. For example, String.Format("%*d", padding, myInt) will print the value of your integer myInt and pad it with padding number of spaces; e.g. if myInt is 45 and padding is 4, this expression will construct a string " 45" (two spaces and 45, padded to 4 characters in total).

Finally, we can do the drawing.

// Check if ammo 1 is valid:

if (am1)

{

// Draw an icon:

DrawTexture(am1.icon,

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize);

// Draw the amounts, and pad them with spaces:

DrawString(my_BigFontMono,

String.Format("%*d/%*d", padding, am1amt, padding, am1.maxamount),

// Offset the text horizontally by the icon's width,

// and vertically by 25% of the font's height:

pos + (iconsize.x, my_BigFontHeight*0.25),

flags);

// Shift the vertical position at the end,

// in case ammo 2 also exists and will need

// to be drawn after this:

pos.y += iconSize.x;

}

// Draw ammo 2's icon and text the same way:

if (am2)

{

DrawTexture(am2.icon,

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize);

DrawString(my_BigFontMono,

String.Format("%*d/%*d", padding, am2amt, padding, am2.maxamount),

pos + (iconsize.x, my_BigFontHeight*0.25),

flags);

}

Let’s review the whole function:

void My_DrawCurrentAmmo(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

let [am1, am2, am1amt, am2amt] = GetCurrentAmmo();

// Stop here if there's no current ammo:

if (!am1 && !am2) return;

// Icon size and offsets:

Vector2 iconSize = (my_BigFontHeight, my_BigFontHeight);

Vector2 iconOfs = (iconSize.x * 0.5, iconSize.y * 0.5);

// Find out which of the current ammo types has the

// biggest maximum amount:

int biggestAmt = max (am1? am1.maxamount : 0, am2? am2.maxamount : 0);

// Construct a dummy "current/max" string using that amount:

String dummyString = String.Format("%d/%d", biggestAmt, biggestAmt);

// And get that string's pixel width in our font:

int ammoStringWidth = my_BigFontMono.mFont.GetCharWidth("0") * dummyString.Length();

// Shift draw position left by ammo string width + icon width:

pos.x -= ammoStringWidth + iconSize.x;

// Check how many ammo types we have:

int ammoTypes;

if (am1) ammoTypes++;

if (am2) ammoTypes++;

// Shift draw position up by icon height multiplied by ammo types:

pos.y -= iconSize.y * ammoTypes;

// Calculate how much we'll need to pad strings based

// on the length of the largest amount string:

int padding = String.Format("%d", biggestAmt).Length();

// Check if ammo 1 is valid:

if (am1)

{

// Draw an icon:

DrawTexture(am1.icon,

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize);

// Draw the amounts, and pad them with spaces:

DrawString(my_BigFontMono,

String.Format("%*d/%*d", padding, am1amt, padding, am1.maxamount),

pos + (iconsize.x, my_BigFontHeight*0.25),

flags);

// Shift vertical position for the next ammo type:

pos.y += iconSize.x;

}

// Draw ammo 2's icon and text the same way:

if (am2)

{

DrawTexture(am2.icon,

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize);

DrawString(my_BigFontMono,

String.Format("%*d/%*d", padding, am2amt, padding, am2.maxamount),

pos + (iconsize.x, my_BigFontHeight*0.25),

flags);

}

}

Just like before, don’t forget to make sure it’s actually present in your Draw() override:

override void Draw(int state, double TicFrac)

{

Super.Draw(state, TicFrac);

if (state == HUD_None || state == HUD_AltHUD)

{

return;

}

BeginHUD();

// Draw health and armor:

My_DrawHealthArmor((4, 0), DI_SCREEN_LEFT_BOTTOM);

// Draw current ammo:

// (we'll push it a little to the left so it's not

// completely flush with the screen's edge):

My_DrawCurrentAmmo((-4, 0), DI_SCREEN_RIGHT_BOTTOM);

}

Let’s take a look at it in the game:

Success!

Colorizing ammo numbers

Just like with health and armor numbers earlier, you might want to colorize your ammo numbers. However, this is a little more complex with the approach we’ve chosen, because the translation parameter of DrawString() applies to the whole string, and you probably want to colorize the current and the max amounts separately. Inline string colorization can only be done with \c color codes as described here on the wiki.

Thankfully, these color codes can be added to the string dynamically, using String.Format(). So, first, we’ll need to make a function that returns a color code. We’ll make this function so it takes amount and maximum amount as input values, and then returns one of the colors based on the ratio of amount to maxamount:

// Amount and maxamount will be the function's

// input values:

String My_GetAmmoColorCode(int amount, int maxamount)

{

// half or more:

if (amount >= maxamount*0.5)

{

return "\cd"; //green

}

// quarter or more:

else if (amount >= maxamount*0.25)

{

return "\ck"; //yellow

}

// less than a quarter but more than 0:

else if (amount > 0)

{

return "\cg"; //red

}

// 0 ammo left:

return "\cr"; //dark red

}

Now, let’s take a look at how we’ve been printing the ammo amount strings so far:

String.Format("%*d/%*d", padding, am1amt, padding, am1.maxamount)

This will output something like “475/600” if am1amt is 475 and am1.maxamount is 600. Now we want to colorize this. I want to colorize only the first part; then I want to make the / character dark-gray, and the maxamount (which is a fixed value) — gray.

We’ll be using the following expression:

String.Format("%s%*d\cu/\cc%*d", My_GetAmmoColorCode(am1amt, am1.maxamount), padding, am1amt, padding, am1.maxamount),

Here’s what’s happening:

-

the first color code is

%s, which pulls a string fromMy_GetAmmoColorCode(am1amt, am1.maxamount)— this%swill get converted into our color code, such as\ck,\cgand so on; -

it’s followed by

%*dwhich is our number (am1amt) padded to thepaddingnumber of spaces (just like we already did before); -

then

\cu/prints a “/” character, colored dark-gray; -

then

\ccsets color to gray; -

and it’s followed by

%*dwhich is our second number (am1.maxamount) padded topaddingnumber of spaces.

We’ll use the same format for the second ammo string. Here’s how our ammo drawing function looks now:

void My_DrawCurrentAmmo(Vector2 pos, int flags)

{

let [am1, am2, am1amt, am2amt] = GetCurrentAmmo();

// Stop here if there's no current ammo:

if (!am1 && !am2) return;

// Icon size and offsets:

Vector2 iconSize = (my_BigFontHeight, my_BigFontHeight);

Vector2 iconOfs = (iconSize.x * 0.5, iconSize.y * 0.5);

// Find out which of the current ammo types has the

// biggest maximum amount:

int biggestAmt = max (am1? am1.maxamount : 0, am2? am2.maxamount : 0);

// Construct a dummy "current/max" string using that amount:

String dummyString = String.Format("%d/%d", biggestAmt, biggestAmt);

// And get that string's pixel width in our font:

int ammoStringWidth = my_BigFontMono.mFont.GetCharWidth("0") * dummyString.Length();

// Shift draw position left by ammo string width + icon width:

pos.x -= ammoStringWidth + iconSize.x;

// Check how many ammo types we have:

int ammoTypes;

if (am1) ammoTypes++;

if (am2) ammoTypes++;

// Shift draw position up by icon height multiplied by ammo types:

pos.y -= iconSize.y * ammoTypes;

// Calculate how much we'll need to pad strings based

// on the length of the largest amount string:

int padding = String.Format("%d", biggestAmt).Length();

// Check if ammo 1 is valid:

if (am1)

{

// Draw an icon:

DrawTexture(am1.icon,

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize);

// Draw the amounts, colorized and padded:

DrawString(my_BigFontMono,

String.Format("%s%*d\cu/\cc%*d", My_GetAmmoColorCode(am1amt, am1.maxamount), padding, am1amt, padding, am1.maxamount),

pos + (iconsize.x, my_BigFontHeight*0.25),

flags);

// Shift vertical position for the next ammo type:

pos.y += iconSize.x;

}

// Draw ammo 2's icon and text the same way:

if (am2)

{

DrawTexture(am2.icon,

pos + iconOfs,

flags|DI_ITEM_CENTER,

box: iconSize);

// Draw the amounts, colorized and padded:

DrawString(my_BigFontMono,

String.Format("%s%*d\cu/\cc%*d", My_GetAmmoColorCode(am2amt, am2.maxamount), padding, am2amt, padding, am2.maxamount),

pos + (iconsize.x, my_BigFontHeight*0.25),

flags);

}

}

And here are the results in-game:

Drawing keys

It’s very important to remember that you need to draw keys in your HUD. Doing this is easy, we’ll mostly be using BaseStatusBar’s DrawInventoryIcon() function. However, there are a couple of rules here. The Key class comes with a couple of special functions that you will need to utilize here:

-